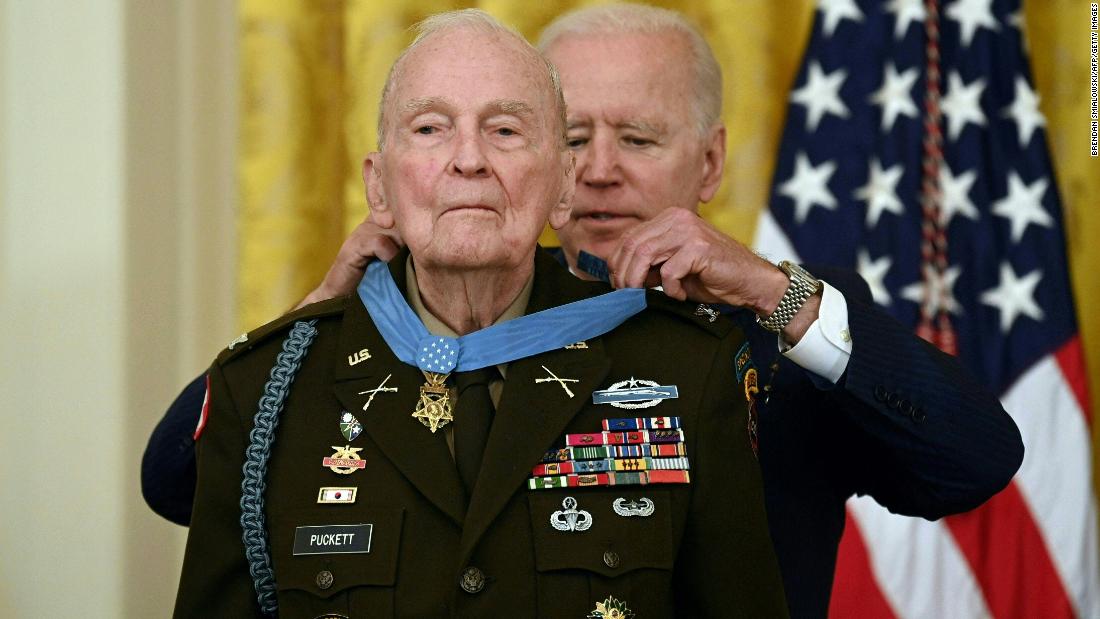

Biden said that Puckett’s initial reaction to receiving the Medal of Honor was to ask, “Why all the fuss? Can’t they just mail it to me?” Biden said that after waiting more than 70 years to be recognized for his heroics, the ceremony was well-deserved.

“Col. Puckett, after 70 years rather than mail it to you I would have walked it to you,” Biden said. “Your lifetime of service to our nation I think deserves a little bit of fuss.”

In the initial daylight assault on the hill, Puckett repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire, rallying pinned down US troops to advance and take the hill from its defenders. But once night fell and temperatures on the hill dropped below freezing, Puckett and his command faced wave after wave of Chinese assaults attempting to retake the key location.

It was estimated that hundreds of Chinese troops were involved in the attack against Puckett’s group of five dozen, he said a video recorded for Witness to War, a compilation of oral histories from veterans.

Sitting atop the hill looking out over the 360-degree perimeter the US forces had set up — with the Chinese lines somewhere in the darkness beyond — Puckett could hear the sound of whistles and bugles.

“That was the way they coordinated with each other,” he said of the Chinese forces. When the notes stopped, “we were hit with a mortar barrage and automatic weapons fire and shortly thereafter a shower of hand grenades.”

Puckett radioed in an artillery strike, stopping the Chinese advance. But a grenade fragment had left him with his first wound of the night.

That assault was the first of what would be six attacks on the US Rangers’ perimeter into the early hours of November 26.

“We were getting more and more pressure and had more and more people wounded” with each assault, Puckett said.

Despite being wounded a second time, through five assaults Puckett was able to call on artillery, firing on points he determined in advance to hold off the Chinese troops.

“They were the overwhelming force that saved our goose,” he said.

Between 2 a.m. and 2:30 a.m., Puckett said the Chinese whistles and bugles sounded again.

He radioed for another round of artillery but got bad news: the big guns had another mission, and Hill 205 would have to wait, the artillery unit said.

“We’re crumbling. We’re being overrun. I just gave my unit the order to withdraw,” Puckett radioed back.

His personal situation was dire. By now, he had been wounded three times and was lying in a foxhole “unable to do anything.”

“I could see three Chinese about 15 yards away from me and they were bayoneting or shooting some of my wounded Rangers,” he recalled.

Then hope ran up the hill.

“All of a sudden, two of my Rangers charged up the hill — Pfc. Billy G. Walls, Pfc. David L. Pollack — they shot the three Chinese, killing them I assume,” Puckett said.

The soldiers came over to their wounded commander.

“Walls said, ‘Sir, are you hurt?’ I thought that was the dumbest question I’d ever heard in my life,” Puckett said.

But aloud to the private Puckett said only, “I’m hurt bad. I can’t move. Leave me behind.”

Walls ignored Puckett’s order and scooped him up, threw him over his shoulder and began running down the hill as Pollack provided covering fire.

They’d gone about 150 yards when Walls put Puckett down, saying he was too heavy to carry, Puckett recalled.

Each private then grabbed a wrist and dragged their commander the rest of the way down Hill 205 on his backside.

“Not very ceremonially, but we made it,” Puckett said.

They found cover with three US tanks, from which Puckett was able to call in a final artillery strike of white phosphorous and high explosives on the Chinese troops now occupying the hill.

“I certainly am pleased that Walls and Pollack disobeyed my order to leave me behind on the hill,” Puckett said.

Puckett “distinguished himself by acts of gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty,” the White House citation says. “(His) extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of military service.”

While that night stands out for Puckett’s heroism, it also marked the beginning of a difficult two years for US forces in the Korean War.

Chinese attacks across the peninsula eventual pushed the US forces and their United Nations allies back into South Korea. At one point, the southern capital of Seoul fell to Communist forces for the second time in months.

“The setback would cause the war to grind on for two and a half more years before ending in an uneasy Armistice on July 27, 1953,” an Army history says.

That armistice, resulting in the Korean Peninsula being divided between North and South along the 38th parallel, persists to this day.

“Korea is sometimes called the forgotten war, but those men who were there under Lt. Puckett’s command will never forget his bravery,” Biden said. “They’ll never forget that he was right by their side through every minute of it. The people of the Republic of Korea haven’t forgotten.”

South Korean President Moon Jae-in attended the ceremony, the first time a foreign leader has attended such an event. He lauded Puckett and said he and other American soldiers helped ensure his nation’s freedom and democracy.

“Col. Puckett is a true hero of the Korean War. With extraordinary valor and leadership, he completed missions until the very end, defending Hill 205 and fighting many more battles requiring equal valiance,” Moon said. “Without the sacrifice of veterans including Col. Puckett and the Eighth Army Rangers Company, the freedom and democracy we enjoy today couldn’t have blossomed in Korea.”

Born in Tifton, Georgia, in 1926, Puckett had a long career in the US military, first enlisting as a private in 1943 during World War II. He was discharged in June 1945 to attend the US Military Academy at West Point, graduating four years later with a commission as a second lieutenant.

After Korea, he also served an 11-month combat tour in Vietnam in 1967-68 in the 101st Airborne Division before retiring from active duty in 1971 with the rank of colonel.

As a retiree, Puckett remain actively involved with the military affairs and in 1992 was one of the first people to be inducted into the US Army Ranger Hall of Fame.

Puckett was originally awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Hill 205, but John Lock, a retired US Army officer and assistant professor at the US Military Academy, came across Puckett’s story during research in the early 1990s and thought it met the criteria for the Medal of Honor, according to an account on the Army’s website.

In 2003 Lock began a process to get Puckett the Medal of Honor, but the petition was denied in 2007 and again on appeal in 2009, according to the report.

Lock persevered, submitting a petition for an upgrade for Puckett after the military ordered a review of all awards in 2016.

After that was denied, Lock was told of alternate route, through the Army award corrections board. That was successful and last year the Medal of Honor for Puckett was approved, but Lock stressed that it was something that Puckett never pushed for.

“As we were going through the process and dead in the water, he appealed to me to stop because he didn’t want me to continue wasting my time,” Lock told the Army website.

24World Media does not take any responsibility of the information you see on this page. The content this page contains is from independent third-party content provider. If you have any concerns regarding the content, please free to write us here: contact@24worldmedia.com